Stephen Pevar's long career at the ACLU came to a close last month. We looked back at some of groundbreaking work.

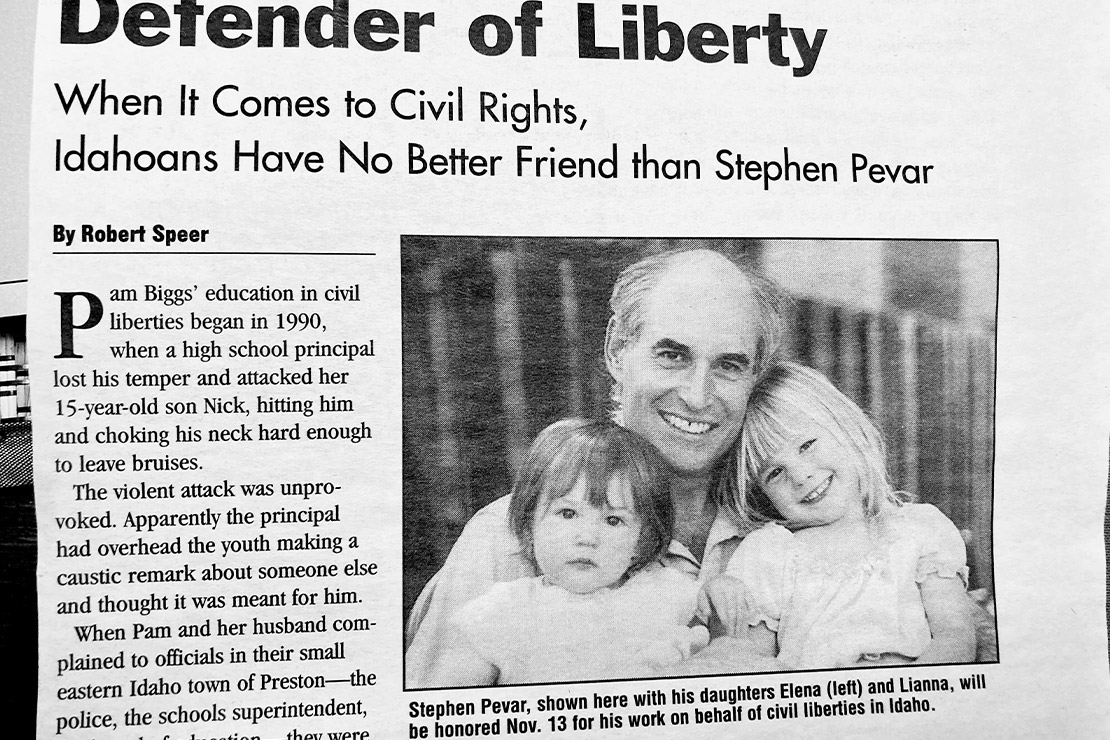

When Stephen Pevar joined the ACLU in 1976, he was one of only 15 national staff attorneys. Over the next 45 years, he filed more than 175 cases — winning or settling more than 90 percent of them — as the organization expanded to a workforce that spans every state, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico, with more than 75 staff attorneys at the national office alone. Last month, he retired as one of the ACLU’s longest-serving staff members.

Following his departure, we sat down with Stephen to discuss big wins and memorable moments from his decades-long career — almost half the ACLU’s 102-year existence — spearheading our Indigenous justice work across the country.

How did you get your start as an ACLU attorney?

My legal career began in 1971 as a Legal Aid attorney on the Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where I worked for nearly four years. During that time, I was selected by the ACLU to become a member of the ACLU’s Indian Rights Committee (IRC), which had just been formed to develop a proposed policy for the ACLU on tribal rights. I got to know the ACLU and the ACLU got to know me from my work on the IRC. When a position in the Mountain States Offices (MSO) opened in 1976, I applied for it and was hired. At the MSO, I was the only staff attorney — national or affiliate — in an 11-state region. It was a great job because I was able to take a lot of different cases in those 11 states. In 2000, the national office closed the MSO because all 11 states now had staff attorneys, and I soon joined the newly-created Racial Justice Program at national as a staff attorney under the leadership of Dennis Parker.

What issues have you worked on?

I’ve worked on a huge range of issues, including free speech, separation of church and state, prisoners’ rights, voting rights, Indigenous justice, and Title IX parity, among others.

What was your first case? What are some of your most memorable cases?

My first ACLU case was a racial justice case. Two months after I started my job, I filed a Title VIII housing discrimination case in Minot, North Dakota on behalf of a Black woman denied housing on the basis of race. The defendants settled the case and our client received damages.

A few months later, I filed two more cases, both totally different from the first case and from each other. One of them, U.S. ex rel. Means v. Solem, was a free speech case on behalf of Indian activist Russell Means. The issue was whether he had a free speech right to engage in a political demonstration despite being on bail. The court ruled in our favor. In the other, Cardiff v. Bismarck Pub. Sch. Dist., the North Dakota Supreme Court held that a “free public education” as guaranteed in the state constitution prohibited a school district from charging parents for their children’s school books. Both cases established important principles in two different states involving key civil liberties issues (freedom of speech, and access to a free and equal education).

Can you name a few of your most significant wins?

I had more than 100 wins that I consider significant. In fact, more than 100 of my cases resulted in reported decisions. As the only ACLU attorney in 11 states, I was very selective (and turned down 500 cases for every one I took). The ones I took were significant.

I also handled intake from those 11 states. I received hundreds of letters every year seeking ACLU assistance, and I answered all of them. In many instances, I sent letters to government officials on behalf of the client when litigation wasn’t possible for our office. Much of what I accomplished was as a result of those letters, in addition to my litigation.

Also, I sued nearly a third of the jails in Wyoming and in Idaho. Many counties in those states opted to improve their jails, rather than be sued and pay attorneys’ fees. These lawsuits resulted in an overhaul of the jail system in those states. Similarly, I sued school districts in Idaho to half the practice of distributing bibles to students and, after winning the first several cases, the practice came to a halt. As for individual cases, here are a few:

● Board of Pardons v. Allen (1987): This was the one case I argued in the Supreme Court. The court ruled in our favor, holding that a Montana parole statute created a protected liberty interest in release on parole and, therefore, prisoners denied parole must be notified of the reasons they were denied.

● Missouri Knights of the KKK v. Kansas City (1989): In this case, the court ruled that the KKK had a free speech right to appear on a municipal public access cable channel on the same basis as everyone else. When Caroline Kennedy and Ellen Alderman wrote “In Our Defense: The Bill of Rights in Action” in 1992, they featured this case and discussed my role in it.

● Ridgeway v. Montana High School Athletic Ass’n. (1990): This was the first statewide class action Title IX case that sought (and obtained) substantial equality in high school athletics for girls. This case changed high school athletic programs throughout the state and guaranteed parity.

● Spiering v. City of Madison (1994): Tom Spiering was a career law enforcement officer who was fired after he blew the whistle on a corrupt supervisor. After a four-day trial, the court found in his favor on free speech grounds. In an earlier free speech case in the same court, Wolf v. City of Aberdeen, the court found that five employees of the city’s fire department had been punished in violation of the First Amendment for speaking on a matter of public concern.

● Yellowbear v. Lampert (2014) and Miller v. Murphy (2008): Both cases were filed against officials at the Wyoming State Penitentiary and both were settled favorably. In Yellowbear, we obtained a consent decree requiring prison officials to allow a Native American religious adherent to possess up to four eagle feathers in his cell for use in religious ceremonies. In Miller, we obtained a consent decree requiring prison officials to accommodate the needs of Muslim prisoners to Halal meals and to pray at certain times without forfeiting their meals.

● Oglala Sioux Tribe v. Van Hunnik (2015): In this case, the district court found that state welfare officials had repeatedly violated the Indian Child Welfare Act and the Due Process Clause, resulting in the unlawful removal of 823 American Indian children from their families, and ordered systemic changes. The remedial order was reversed on appeal, however, on abstention grounds. Despite the reversal, state welfare officials continue to implement all of the procedures that the district court held were required by federal law.

How have you seen the ACLU evolve during your 45-year career?

By far the greatest evolution is one of size. The ACLU is probably 50 times larger than when I started working here, both at national and in the affiliates. As a result, we can undertake far more work than we previously could. Another evolution is that the ACLU has become a mainstream and well-known organization, generally respected even by those who disagree with us. That wasn’t the case when I started. At first, few people knew about the ACLU and many who did, despised us. Lastly, the ACLU now litigates in many areas we didn’t previously (or didn’t do nearly as much as today).

What do you see the ACLU looking like in the next 45 years? What works lies ahead?

I hope the ACLU continues to grow at the same rate we have grown during the past 45 years, and that we continue to take many types of cases. One type of case we need to undertake far more frequently than we do is Indigenous justice cases. I would like to see us do far more work in this area.